By Laura Resmini, Vieri Calogero, Simona Comi and Mara Grasseni

UNIMIB Research Team

In the last decades, globalisation has driven firms to re-organise the production process on a global scale, through the so-called global value chains (GVC), where firms located across different countries carry on different stages of the production process.

While Cross-border production is not a new phenomenon, it has expanded rapidly because of the liberalisation of trade and investment, lower transport costs, advances in information and communication technology, and innovations in logistics. The development of GVCs has been driven mainly by multinational corporations (MNEs) localised in industrialised economies, which have sliced up the production process in tasks and functions carried out in different countries for reasons of efficiency and competition. Indeed, foreign affiliates get access to specific resources not available or too costly to obtain in the origin countries and to localised knowledge pools. This knowledge is then transformed, re-used and distributed along the networks benefitting the places where MNEs are headquartered or have relocated the foreign activities.

Therefore, knowing where MNEs are headquartered and where they locate the different production activities gives an idea of the distribution over space of the potential benefits and costs associated with the participation in GVCs.

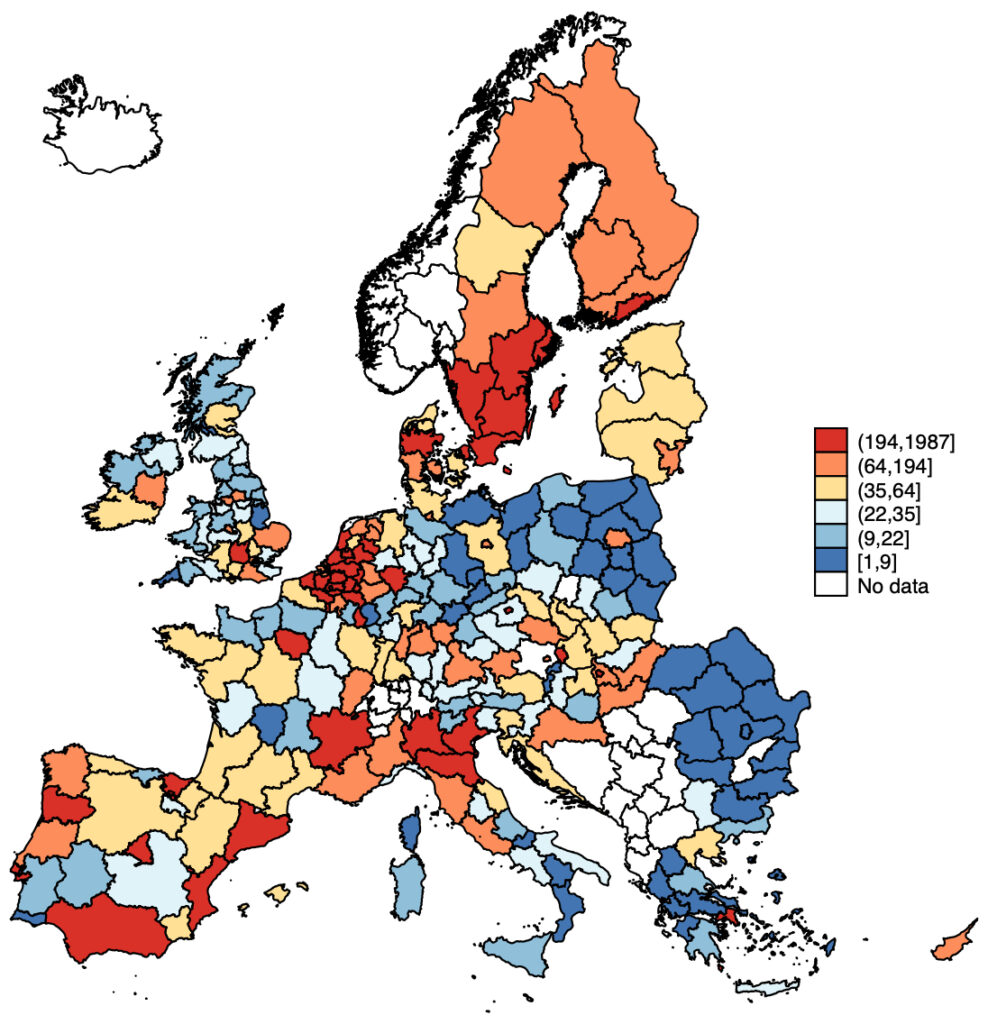

Figure 1 shows where MNEs are headquartered in the EU27+UK member states by NUTS2 regions. In order to map the origin of each MNE we considered where the Global Ultimate Owner (GUO), i.e. the independent firm at the top of the corporate structure is headquartered.

In 2018, we observed about 68,109 GUOs. Given their numerousness, almost every EU region takes part of a GPN, with few exceptions. However, their distribution over space is quite uneven. Indeed, Central and richer EU regions in Western EU member states, like Lombardy in Italy or Cataluña in Spain, host a large number of firms governing GPNs, while Southern and Eastern peripheral regions participate marginally to GVCs, hosting a few MNEs controlling networks of production. Most MNEs chose capital regions as locations for their headquarters.

Whether this uneven distribution leads to an exacerbation of disparities or to catching up processes is still unclear, since we still do not know whether the impact of GPNs on regions’ productivity and income growth is magnified or hampered by contextual factors.

From a policy perspective, this implies that effective policy interventions must take into consideration the structural conditions of different regions. Poor peripheral regions need intervention to improve infrastructure to attract more foreign investors. However, this may not suffice since some tasks may be easily relocated elsewhere. Core regions already well connected with global markets, in contrast, may need policy measures to make administrative procedures at the border faster and more efficient, to help MNEs headquartered in these regions to efficiently control and monitor the production activities within the network.

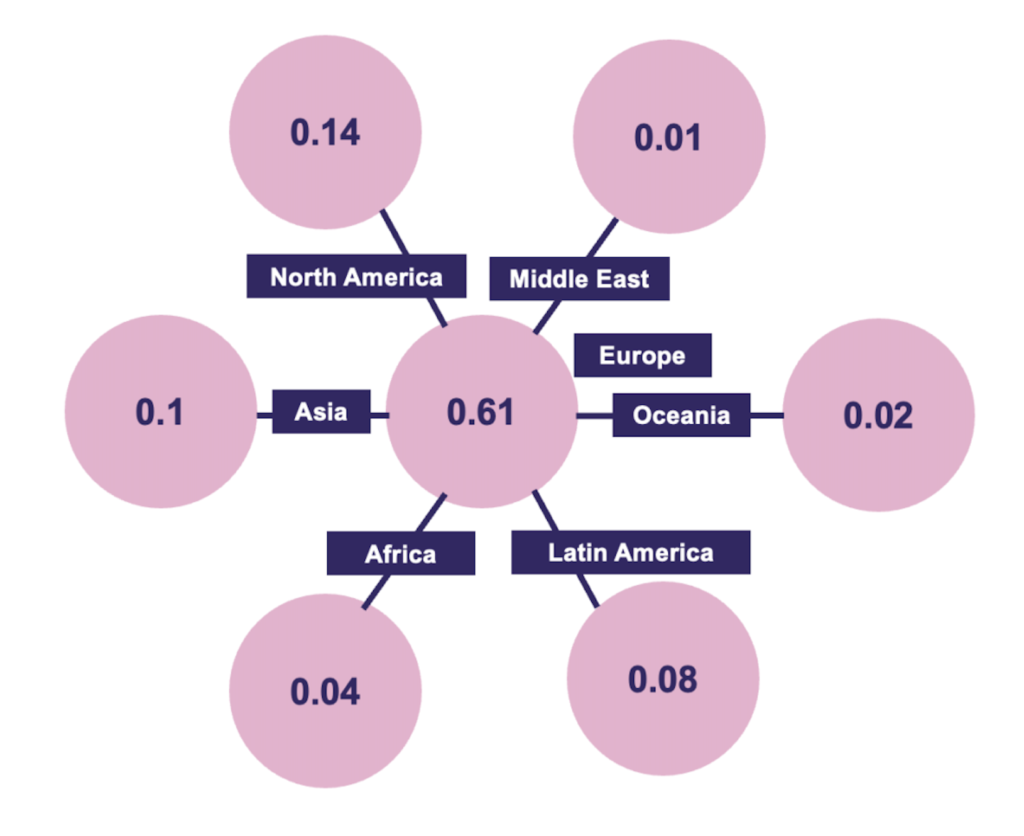

Figure 2 shows where MNEs headquartered in the EU27+UK have relocated their foreign activities. It is apparent that EU-centred GPNs are less global than one can think at first sight. Indeed, about 61% of foreign subsidiaries controlled by EU MNEs operate in European countries other than those where MNEs governing the network are headquartered. Outside Europe, the main destinations are North America (about 14%), Asia (10%), and Latin America (8%), while Africa, Middle East countries and Oceania are only marginally involved in the production activities of EU MNEs. In Asia, main destinations include China, India, Honk Kong, and Singapore.