María-Ángeles Cadarso (UCLM), Ángela García-Alaminos (UCLM), Jorge Zafrilla (UCLM), Nuria Gómez (UCLM), Maria-Ángeles Tobarra (UCLM)

Since the 2008 global crisis, global trade has shifted towards deglobalization, with Global Value Chains (GVCs) becoming shorter and more regional. Recent shocks have accelerated this trend, exposing GVC vulnerabilities and prompting governments and firms to seek greater resilience and sustainability. This has led to reshoring - bringing production back home (backshoring) or to nearby friendly countries previously outsourced to low-wage regions (nearshoring). The environmental impact of these changes is crucial, as it can either support or hinder climate efforts.

Despite overall emission reductions post-crisis, changes in EU supplier geography have increased carbon emissions, counteracting climate efforts. Supplier shifts contributed 23.4% of carbon footprint growth pre-crisis (1995-2008) and prevented a potential 6% reduction post-crisis (2009-2018).

However, reshoring and nearshoring can align GVC resilience with climate goals. Reshoring five strategic products—iron and steel, electrical motors and batteries, chips and circuits, antibiotics, and vaccines—can reduce the EU's carbon footprint. Although these imports are less than 1% of total EU imports, significant emission reductions are found, especially in iron and steel supply chains, with a 4.0% reduction in the basic metals industry's carbon footprint contribution and 9.0% for imported counterparts.

Territorial emission impacts are minimal for the EU and member states, though slightly higher in Eastern EU countries. Additionally, in basic metals, backshoring reduces emissions more than nearshoring. For chips and circuits, and electric motors and batteries, nearshoring saves more emissions than backshoring.

Ignoring carbon emissions in trade and GVC reconfiguration will increase global emissions. The EU must integrate environmental considerations into trade policy, setting emissions and carbon footprint targets in agreements. This approach can create synergies between GVC resilience and climate goals. Lower emissions are already influencing new GVC trends, with reshoring and reoffshoring showing lower emissions than previous offshoring.

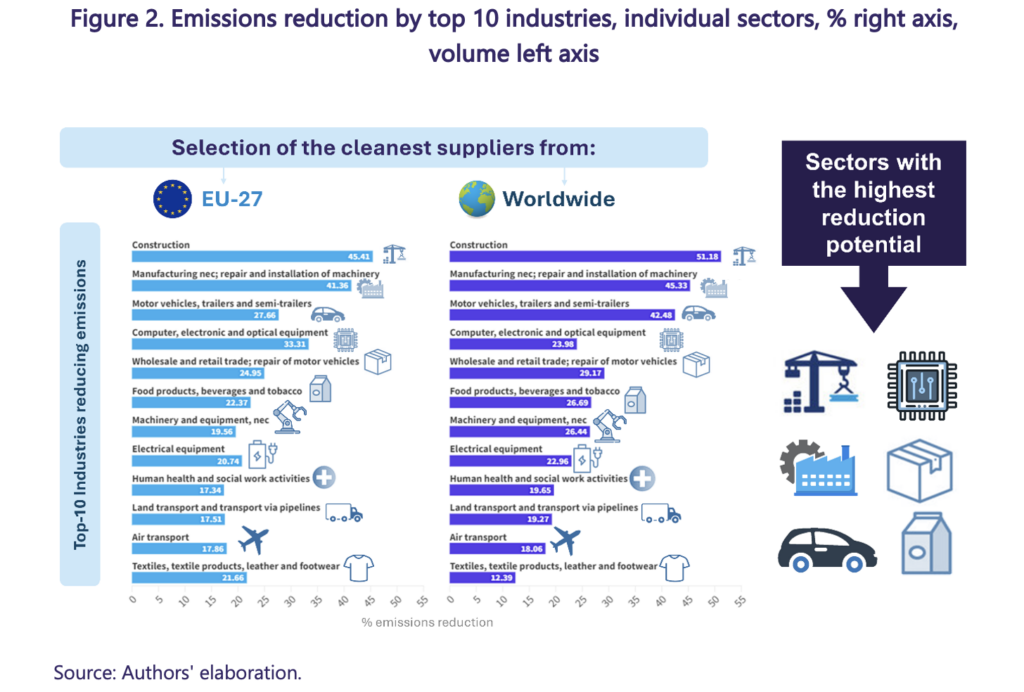

Selecting suppliers based on low carbon emissions, or greensourcing, can significantly reduce emissions, especially if all sectors adopt this strategy. Key sectors for emission reductions (Figure 2) include construction, manufacturing, machinery repair, motor vehicles, and electronics. Reshoring these industries from more polluting countries improves the EU's carbon footprint. Emission reductions are greater when considering the most efficient global suppliers (scenario 5) rather than limiting to EU suppliers (scenario 4) (51.18% and 45.41% in construction, for instance).

However, resource shuffling could negate these benefits if cleaner EU production leads other countries to use dirtier suppliers, potentially increasing global emissions by 0.5%.

EU efforts must be globally contextualised. Policies should ensure low-cost-based incentives and the uptake of low-carbon technologies, circular economy potential, and high supply security and quality drive GVC reconfiguration. Achieving resilience and sustainability requires effective regulations, circular business models, skilled workers, and appropriate technologies enabling cost-effective solutions.