Louise Curran (TBS), Christian Gnekpe (TBS), Thibaut Joltreau (TBS), and Torben Pedersen (CBS)

Work Package 4 examined the challenges currently faced by circular initiatives across two countries (France and Denmark) and several sectors. Despite differences in national policy and industrial contexts, we identified numerous common challenges to integrating circularity principles into firms' business models, such as high costs, the practical and regulatory difficulties of reverse logistics, and the difficulties posed by the fact that the composition of pre-used materials is often unknown. The need for novel approaches in 'non-linear' systems also requires new types of intermediaries to connect and support the many different actors who need to collaborate within and across values chains.

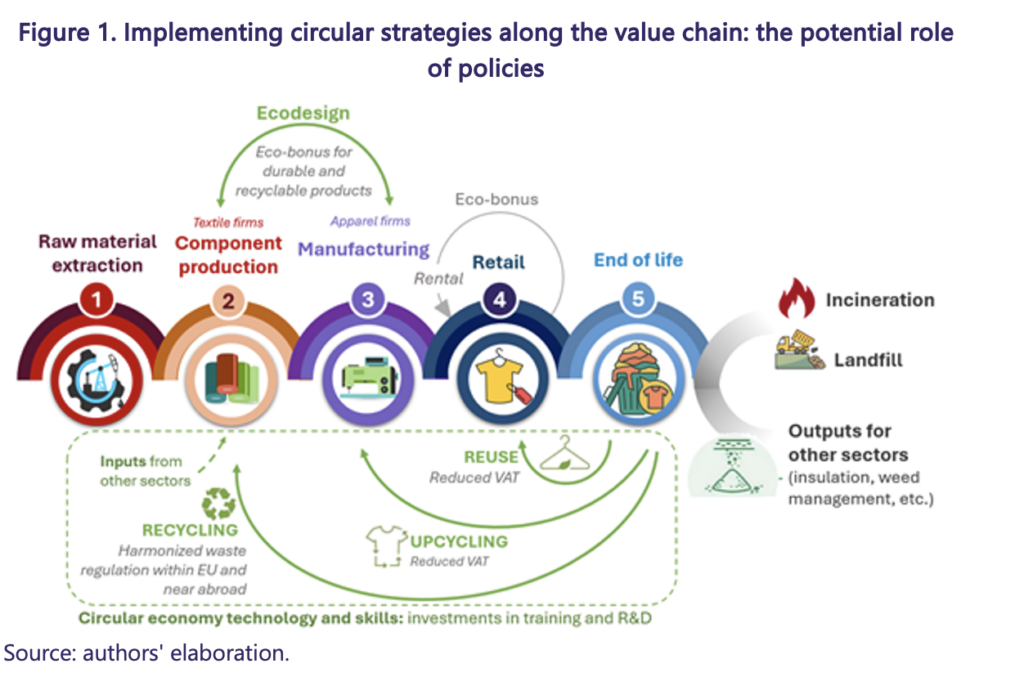

The research revealed that while reuse is the most desirable approach from a circularity perspective, it is rarely the most attractive in terms of costs or business capability. Indeed, a key conclusion emerging from the work is that the market often favors the least sustainable solutions. Therefore, policy measures are needed to better incentivise the most environmentally beneficial circular approaches. While each sector has specific needs, addressing the remaining barriers to EU-level waste flows, providing robust incentives for managing end-of-life products for all firms on the EU market, and investing in both skills and reconditioning/recycling capacities are critical to scaling the circular model across industries. Although policy measures can encourage shifts in commercial and consumption patterns, ultimately, success depends on firms' willingness to embrace circular business models and consumers' readiness to favour products designed for and through circularity.

The key policy proposals for EU and national actors emerging from our work on the circular economy include:

- Public support for intermediaries: Intermediaries are vital to providing the research, advice and networking services that facilitate the transition to circular practices, yet they struggle to secure economic viability. One pathway to fund such services is through Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), where companies are held accountable for the end-of-life of their products and pay 'eco-contributions' to cover these costs. France has seen some positive – although limited – results with this approach, but alternative financing options should also be explored.

- Fostering cooperation across and within industries: Promoting collaboration across industries can improve efficiencies and increase scale. In most cases, it would be more efficient to build sectoral or cross-sectoral solutions to collect end-of-life products instead of each firm or Global Value Chain building their own reverse logistics system. Public support may be necessary to kick-start such initiatives.

- Scaling circular initiatives: If they are to be economically viable, circular initiatives need to scale up, while extracting the value from pre-used material requires more sorting capacity for end-of-life products. To achieve the required scale, investment needs to be incentivised, including by harmonising waste regulation at the EU level and creating a single EU market in used, reconditioned and waste products.

- Investment and innovation: Market harmonisation needs to be combined with policy support for investment, especially in technological innovation, which many stakeholders view as vital to enabling the shift to cost-effective and efficient circular solutions.

- Regional cooperation: Expanding cooperation with neighboring regions, particularly the pan-Euro-Mediterranean area, could also support scale economies. These regions are already integrated into EU value chains and offer both geographic and geopolitical advantages. Barriers to moving end-of-life products across borders in this region could be addressed by negotiating bilateral mutual recognition agreements with key trade partners. Such agreements could be integrated into the 'Clean Trade and Investment Partnerships' to be launched by the new Commission.

- Incentives and disincentives for circular firms: Both 'born-circular' firms and circular initiatives within lead firms struggle to secure profitability. Greater incentives and disincentives are needed if circular economy practices are to become mainstream. This could include requiring producers of less durable, harder-to-recycle products to pay higher eco-contributions to fund end-of-life costs, or levying reduced VAT (or import tariffs) on reconditioned or second-hand goods. This could help to improve the economics of these new circular business models.

- Regulatory standards: Regulations imposing minimum standards are essential to driving the circular transition forward. Ecodesign norms on the EU market are potentially powerful tools. They could require all actors to develop more durable, repairable and ultimately recyclable products. However, carefully defining the criteria for these norms will be key to their success.

- Skills development: Europe currently lacks expertise and skills in several key areas vital to the circular transition. Adequate training and re-skilling efforts are essential to developing a robust, EU-based circular industry.

Figure 1 below highlights the key policy interventions proposed here, as well as the stage in the values chain where they have the strongest impact.